US blood was too freely imported to UK in 70s and 80s, David Owen tells inquiry

US blood was too freely imported to UK in 70s and 80s, David Owen tells inquiry

Ex-health minister says not enough was done to avoid using contaminated US blood to treat haemophiliacsEx-health minister says not enough was done to avoid using contaminated US blood to treat haemophiliacsNot enough was done to stop contaminated blood being imported from the US to treat haemophiliacs in Britain in the 1970s and 80s, the former UK health minister David Owen has said. Giving evidence to the infected blood inquiry, the former Labour MP said he had supported making Britain self-sufficient in blood products and had been determined to “stop blood coming in from America”.

The inquiry, set up in 2017, is examining how 30,000 people became severely ill after being given contaminated blood products, imported from the US, in the 1970s and 80s; about 3,000 haemophiliacs have since died. It is being held live in Fleetbank House, central London, with participants wearing masks when not talking. It is also being streamed online.Lord Owen was a minister at what was then the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) from 1974-76 or, as he said it was known, the “department of stealth and total obscurity”. The use of factor 8 – derived from blood – to prevent haemophiliacs bleeding was still a relatively new treatment at the time.

Owen, who strongly favoured a policy of “self-sufficiency” in sourcing blood products for haemophiliacs from voluntary donations made through blood transfusion services in Britain, initiated a £500,000 programme to boost domestic production. The dangers caused by taking donations from paid donors, as happened in the US, were well known even then, Owen told the inquiry. Donors paid money were less likely to answer questions truthfully about whether they had previously had jaundice, other illnesses or were drug addicts, he said.

Guardian Today: the headlines, the analysis, the debate - sent direct to you Read more“We should have realised how dangerous it was to rely on blood coming in from abroad from people who were given blood for money,” Owen said. The problem was that “we were not getting enough from our own transfusion service”. Owen told the inquiry: “I didn’t sit on [all the medical committees at the DHSS] but I didn’t envy [the doctors on] them. It’s possible that the wrong decisions were taken ... It would have been an abuse of my power to interfere with the [clinical] decision making. What I felt was that you had to stop this blood coming in from America.”

Parliament was never told the government later moved away from a policy of self-sufficiency, he said. “It was a pledge [to pursue self-sufficiency]. I have always said you could not move away from self-sufficiency without going back to parliament.” Owen said he was surprised in the mid-1980s to see his successor at the department announce that the government had decided in 1982 to introduce a policy of self-sufficiency. “So what was happening in all those six years after I left the department in 1976?” he asked the inquiry.

Part of the problem was that doctors switched to prophylaxis: prescribing factor 8 regularly to prevent haemophiliac patients bleeding before they had an accident. That medical approach required more blood products. The World Health Organization even in the 1970s was recommending avoiding paying for blood donations or relying on commercial blood supplies. Owen, 82, said: “There were some who preferred to go on taking commercial products even when there was increased [domestic] production.” The aim was for NHS self-sufficiency by 1977, he said. “It ought not to have been allowed to slip into the 1980s.”

That policy would have continued after he left the department, Owen said. “It’s extraordinary to find that the whole of my private office records were pulped. The documentation in the private office was part of the continuing pledge.” The files, it is thought, were destroyed in 1988. Self-sufficiency was a policy that should have been followed not just in blood products, Owen said. “When will we learn that there are certain assets you need to control inside your own country?”

The inquiry was read a letter to the department by Dr Rosemary Biggs, of the Oxford Haemophiliac Service, written in 1967, who warned that commercial products would soon be available from the US and that “we may be obliged to buy it at a very high cost to our patients”. It was not clear whether that was a reference to risk or financial cost.

Earlier, opening the new session of hearings, its chair, Sir Brian Langstaff, said: “Those of you who have come in person … in such numbers, despite the perils of the pandemic, itself tells a story. It emphasises how important the issues are to you. It shows the value of these hearings.” Since you’re here ...… we have a small favour to ask. Millions are flocking to the Guardian for open, independent, quality news every day, and readers in 180 countries around the world now support us financially.

We believe everyone deserves access to information that’s grounded in science and truth, and analysis rooted in authority and integrity. That’s why we made a different choice: to keep our reporting open for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay.

The Guardian has no shareholders or billionaire owner, meaning our journalism is free from bias and vested interests – this makes us different. Our editorial independence and autonomy allows us to provide fearless investigations and analysis of those with political and commercial power. We can give a voice to the oppressed and neglected, and help bring about a brighter, fairer future. Your support protects this.

Supporting us means investing in Guardian journalism for tomorrow and the years ahead. The more readers funding our work, the more questions we can ask, the deeper we can dig, and the greater the impact we can have. We’re determined to provide reporting that helps each of us better understand the world, and take actions that challenge, unite, and inspire change.

Your support means we can keep our journalism open, so millions more have free access to the high-quality, trustworthy news they deserve. So we seek your support not simply to survive, but to grow our journalistic ambitions and sustain our model for open, independent reporting.

If there were ever a time to join us, and help accelerate our growth, it is now. You have the power to support us through these challenging economic times and enable real-world impact.

Reference: The Guardian:22/09/2020

Woman, 117, marks becoming Japan's oldest ever person with cola and boardgames

Woman, 117, marks becoming Japan's oldest ever person with cola and boardgames

A 117-year-old woman with a weakness for fizzy drinks and chocolate has become Japan’s oldest person on record, as the country marks a public holiday devoted to its senior citizens.A 117-year-old woman with a weakness for fizzy drinks and chocolate has become Japan’s oldest person on record, as the country marks a public holiday devoted to its senior citizens.

Kane Tanaka, who had already been recognised by the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s oldest living person in March last year, achieved the all-time Japanese age record on Saturday, when she became 117 years and 261 days old.

The supercentenarian, who lives in a nursing home in the south-western city of Fukuoka, beat the previous record, held by another Japanese woman, Nabi Tajima, who died in April 2018 aged 117 years and 260 days.

Related: Making a slow getaway: Japan's anti-yakuza laws result in cohort of ageing gangsters

Tanaka celebrated the achievement with a bottle of Coke – her favourite drink – and wore a T-shirt with her face printed on it that had been given to her by members of her family.

Her grandson, 60-year-old Eiji Tanaka, told the Kyodo news agency that his grandmother was in good health and “enjoying her life every day,” despite restrictions on family visits due to the coronavirus pandemic. “As a family, we are happy and proud of the new record,” he said.Tanaka is not alone in living past 100. New government figures released ahead of Respect for the Aged Day on Monday showed that the number of Japanese aged 65 and over stood at a record-high of 36.17 million, including 80,450 who are aged at least 100.

The number of centenarians rose above 80,000 for the first time, underlining the financial and healthcare challenges posed by the country’s rapidly ageing population, with women accounting for more than 88% of the total, the health ministry said last week. By contrast, the number of Japanese aged 100 or over came to just 153 when the survey was first conducted in 1963.

The over-64s now account for 28.7% of Japan’s population – the highest proportion of any country – according to the internal affairs ministry.

The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research projects that age group will comprise just over 35% of the population by 2040.

The seventh of nine children, Tanaka was born on 2 January 1903, the year the Wright brothers made their first powered flight and the first Tour de France was held. She has lived through the reigns of five Japanese emperors.

Tanaka, who has not been able to meet relatives due to the coronavirus, has reportedly been passing the time playing a board game with other residents.

She is now the third-oldest person ever, behind Jeanne Calment, a Frenchwoman who died in 1997 at the age of 122, and American Sarah Knauss, who died in 1999 at age 119, according to the US-based Gerontology Research Group.

Reference: Justin McCurry in Tokyo 11 hrs ago: 20/09/2020

Coronavirus news - live: UK deaths ‘could reach 200 each day’ as lockdown spreads in Wales amid ‘rapid rise’

Coronavirus news - live: UK deaths ‘could reach 200 each day’ as lockdown spreads in Wales amid ‘rapid rise’

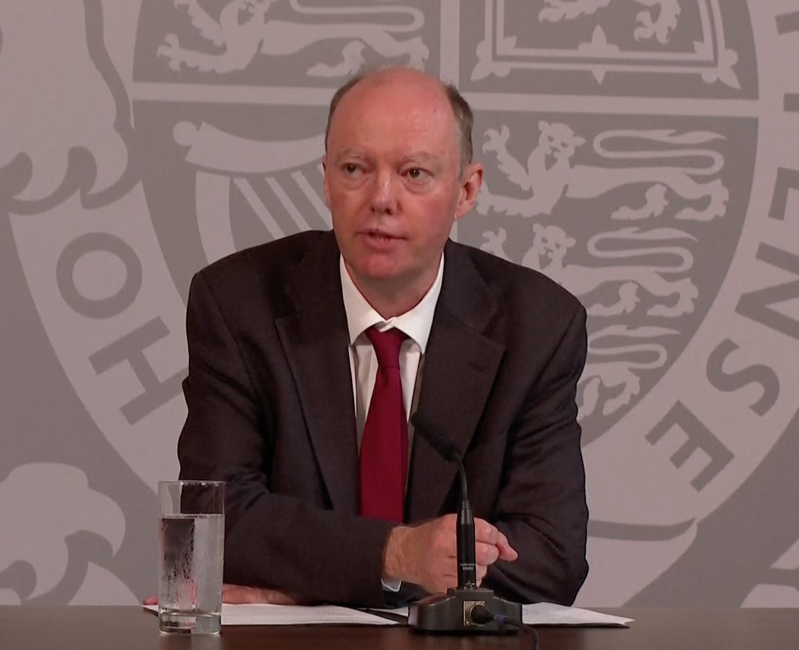

The government’s chief scientific adviser has warned that the UK could see 50,000 new Covid-19 cases per day in mid-October if the current rate of infection is not brought under control, which could lead to 200 deaths a day.The government’s chief scientific adviser has warned that the UK could see 50,000 new Covid-19 cases per day in mid-October if the current rate of infection is not brought under control, which could lead to 200 deaths a day.

Professor Chris Whitty and Sir Patrick Vallance led a televised news briefing on the ongoing health crisis on Monday morning.

Meanwhile, London mayor Sadiq Khan is to meet with council leaders today to discuss stricter lockdown measures for the capital, after the rate of cases in London rose in a seven-day period ending early last week, from 18.8 per 100,000 people to around 25.A spokesperson for Mr Khan said on Sunday that as the “situation is clearly worsening”, the mayor will be seeking “fast action” on imposing more restrictions.

Reference: Independent: Kate Ng 2 hrs ago: 21/09/2020

World Alzheimer’s Day: The cost of caring for someone with dementia

World Alzheimer’s Day: The cost of caring for someone with dementia

Memory loss, confusion and unpredictable mood swings are just a few of the symptoms that characterise Alzheimer’s. To mark World Alzheimer’s Day on Monday, FRANCE 24 spoke with two people each caring for someone with the disease about how it has transformed their lives.Memory loss, confusion and unpredictable mood swings are just a few of the symptoms that characterise Alzheimer’s. To mark World Alzheimer’s Day on Monday, FRANCE 24 spoke with two people each caring for someone with the disease about how it has transformed their lives.

Alzheimer’s is the most common degenerative brain disease and the leading cause of dementia. In France, there are currently 900,000 people living with it. As the country’s population continues to age, an estimated 225,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.The way Alzheimer’s slows the brain means that it affects not only the patient but also their loved ones. While some diagnosed with the disease decline quickly, others require long-term care and support.

Overall, some 3 million people were affected by the disease in France in 2020, according to the Alzheimer’s Research Foundation (Fondation recherche Alzheimer). This number includes patients, healthcare professionals and the hundreds of thousands of family members who act as unpaid caregivers.Here, two people caring for loved ones living with Alzheimer’s share their stories.

Memory loss and difficulty with tasks.Over the last six years, François*, 85, has watched his ability to function gradually decline. His life is punctuated by gaping lapses in memory, which have forced his wife Annie*, 79, to provide him with constant care.

“Today, for example, I asked him to mow the lawn. He’s perfectly capable if I put the lawnmower in his hands, plug it in and turn it on. But it’s utterly impossible for him to do these things on his own,” she told FRANCE 24. “What’s more, it’s difficult for him to grasp how objects work. He wanted to mow the porch, as though the lawnmower were a vacuum cleaner.” Often characterised by the memory loss it causes, Alzheimer’s disease gradually attacks other areas of the brain, and can affect a patient’s speech, as well as their ability to complete simple daily tasks. This can lead to changes in behaviour, that can sometimes take an aggressive turn.

“Nights are particularly difficult,” Christiane*, 73, who cares for her husband Jean-Pierre*, told FRANCE 24. “He wakes up a lot. Sometimes he yells or falls out of bed, but he doesn’t remember any of it. It’s very disorienting because I never know what to expect.” ‘A mental ordeal’ This thing just fell on me so quickly. It was brutal and I wasn’t prepared for it,” Christiane continued.

Her husband was diagnosed this summer after she took him to the hospital because he felt unwell. Since then, his decline has been rapid. “He can’t go to the toilet by himself anymore, I have to be with him constantly. It’s very difficult. I don’t have any training as a nurse and I lose my patience very easily. My life has become hell,” Chistiane said.Meanwhile, Annie has had a very different experience with the disease, which has slowly progressed in her husband over the years.

“Before, I didn’t know anything about Alzheimer’s. Now, what surprises me, in our case, is that it is a slow form of agony,” she said. “Of course it’s better for my husband that the disease progressed slowly… But it’s a mental ordeal.” Like Christiane, Annie often loses patience with her husband. Although it is not unusual for a caregiver to feel this way, according to specialists, it can be hard for them to understand.

“I’m not very likeable, I can’t keep calm, and I can’t control myself in the face of this situation, which is not normal,” Annie said. “It’s stronger than me: I react and then I’m angry with myself. Especially when others are watching. People don’t understand why I’m not more supportive, but it’s hard to let go of everything. They don’t realise how suffocating the situation is.” A growing sense of isolation.

Like many caregivers, Christiane has watched her social life contract following her husband’s diagnosis. A former director of human resources, it has been hard for her to bear. “In my old life, I went out all the time. I exercised and had volunteer activities,” she said. “Now, I hurry when I go grocery shopping, because I’m afraid something will happen. I’m a caregiver. Some people look at me differently now, they wish me good luck. But I don’t need luck, I didn’t choose this situation. I didn’t have a choice.”

Annie has also watched her contact with the outside world wane over the years. “Our circle of friends has grown smaller because my husband can’t communicate in the same way. Fewer people visit us,” she said. “But what really hurts is the distance with family. I can’t go see my son in [the western French town of] Rennes, because I would have to sleep there, which is completely out of the question.” While some Alzheimer’s symptoms can be managed with treatment, there is no cure for the disease. As a result, many caregivers feel helpless to stop its progression.

“The lack of options eats away at me. It’s heartbreaking to know there is no hope,” Christiane explained. “I drag my husband from appointment to appointment, even though it doesn’t do anything. It’s a hypocritical system. I am now living from one day to the next, trying to preserve my health. I never took any medication before, but now I can’t sleep without taking something for anxiety.” ‘I’ll have to sell the house’

There are a number of care centres in France that cater to patients who have lost the ability to function independently, and in particular those with Alzheimer’s. For many caregivers, it can be a welcome breath of fresh air. However, they can be prohibitively expensive.

“In my situation, I have to think of what’s coming next and do my accounting,” Christiane said. “A spot in a care facility costs between €2,500 and €3,000 (per month). It’s the equivalent of our entire monthly retirement payments, so I’m going to have to sell our secondary residence. Degenerative disease is the death of inheritance.” Although Annie has long avoided thinking about it, she is now considering a similar scenario. “I’ll have to sell the house and live elsewhere.

My son is pressuring me to save more money. Up until now, I always tried to maintain a certain form of insouciance. But I’m more stressed this year, I can feel the end is near.” The average life expectancy for a patient with Alzheimer’s is 10 years after the first onset of symptoms. But the disease doesn’t affect everyone in the same way. While some die quickly, others can live for decades in a total state of dependence. *Surnames withheld to protect the identity of those interviewed

Reference: France 24: David RICH 3 hrs ago: 21/09/2020

Articles - Most Read

- Home

- LIVER DIS-EASE AND GALL BLADDER DIS-EASE

- Contacts

- African Wholistics - Medicines, Machines and Ignorance

- African Wholistics -The Overlooked Revolution

- African Holistics - Seduced by Ignorance and Research

- The Children of the Sun-3

- Kidney Stones-African Holistic Health

- The Serpent and the RainBow-The Jaguar - 2

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-3

- 'Tortured' and shackled pupils freed from Nigerian Islamic school

- King Leopold's Ghost - Introduction

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-4

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-2

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-5

- African Wholistics - Medicine

- Menopause

- The Black Pharaohs Nubian Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt

- The Mystery System

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-6

Who's On Line?

We have 133 guests and no members online

Ad Agency Remote

Articles - Latest

- The Male G Spot Is Real—and It's the Secret to an Unbelievable Orgasm

- Herbs for Parasitic Infections

- Vaginal Care - From Pubes to Lubes: 8 Ways to Keep Your Vagina Happy

- 5 Negative Side Effects Of Anal Sex

- Your Herbs and Spices Might Contain Arsenic, Cadmium, and Lead

- Struggling COVID-19 Vaccines From AstraZeneca, BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna Cut Incidence Of Arterial Thromboses That Cause Heart Attacks, Strokes, British Study Shows

- Cartilage comfort - Natural Solutions

- Stop Overthinking Now: 18 Ways to Control Your Mind Again

- Groundbreaking method profiles gene activity in the living brain

- Top 5 health benefits of quinoa

- Chromolaena odorata - Jackanna Bush

- Quickly Drain You Lymph System Using Theses Simple Techniques to Boost Immunity and Remove Toxins

- Doctors from Nigeria 'facing exploitation' in UK

- Amaranth, callaloo, bayam, chauli

- 9 Impressive Benefits of Horsetail

- Collagen The Age-Defying Secret Of The Stars + Popular Products in 2025

- Sarcopenia With Aging

- How to Travel as a Senior (20 Simple Tips)

- Everything you need to know about mangosteen